|

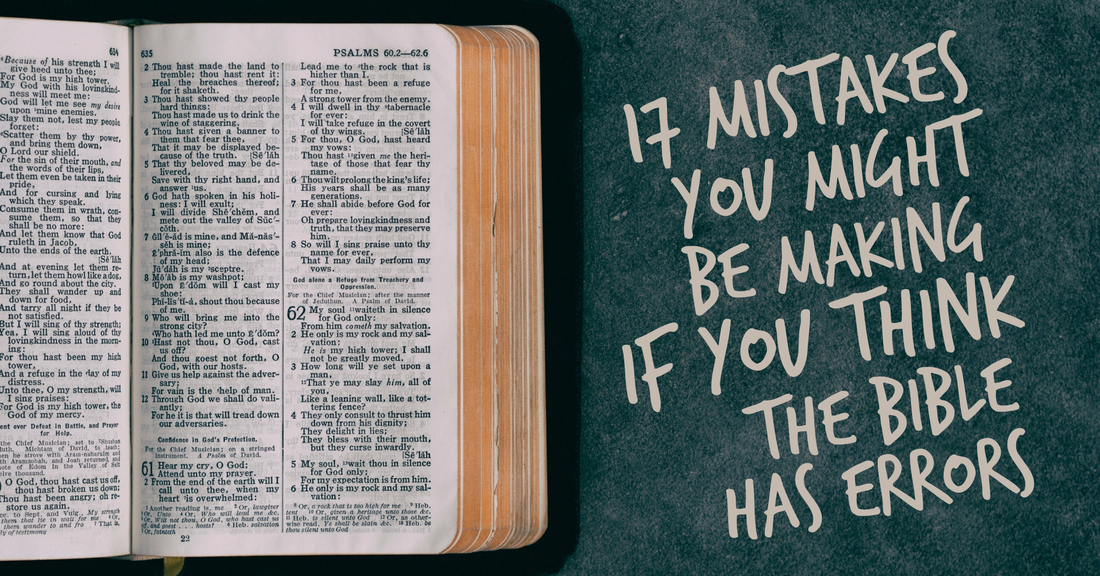

[This post is a summary of the introduction to Making Sense of Bible Difficulties....Clear and Concise Answers From Genesis to Revelation, by Norman Geisler and Thomas Howe.] Many critics claim that the Bible is riddled with errors. They point out differences in the gospel accounts or discrepancies among varying reports of the same historical event. The truth is that Bible does not have errors, but there are certainly some passages that can be difficult to understand, especially if we don't take certain principles into account.

If you think the Bible has mistakes, I'd like to invite you to consider that you might be making one of these 17 mistakes:

1. You might be assuming that the unexplained is not explainable. When scientists come across an anomaly or other unexplained phenomena, they don't simply throw up their hands in defeat, and say, "Well... I guess it must be a contradiction." The same principle applies to biblical research. For example, critics used to say that the first five books of the Bible couldn't have been written by Moses because in Moses' day, writing hadn't yet been invented. But we know now that writing existed for about 2,000 years before Moses' time. 2. You might be presuming the Bible guilty until proven innocent. The typical way people approach human communication is that there is no reason to suspect someone is lying unless they give you a reason to believe so. The Bible should be given the same courtesy. 3. You might be confusing fallible interpretations with infallible revelation. Humans are finite beings, and finite beings can be mistaken. As long as human beings exist, there will be mistaken interpretations of God's Word. This doesn't mean the revelation God gave is wrong—it just may be that the interpreter doesn't understand it. 4. You might be misunderstanding the context of the passage. It can be tempting to read ancient literature through a contemporary lens. The meaning of the text is determined by its context, so imposing modern sensibilities upon a very antiquated and foreign backdrop will almost always lead to misunderstanding. 5. In the case of an unclear verse, you might not be interpreting it in light of the clear ones. This is an aspect of hermeneutics (the study of Bible interpretation) that is so often overlooked by skeptics. If a verse is not particularly clear on a topic, you compare that verse with other relevant verses that are clear and interpret it in light of those. 6. You might be basing a belief on one obscure passage. Some Bible verses are hard to understand because the meaning of a key word appears only once, or very rarely. There is a common mantra in Bible interpretation: "The main things are the plain things, and the plain things are the main things." If something is not plainly taught in Scripture in more than one place, it's probably not a "main thing." 7. You might be forgetting that God worked in unison with human authors. The Bible wasn't dictated by God as if the writers were simply secretaries. God worked in conjunction with their own literary styles, personalities, and cultural contexts. Although the Bible is without error, forgetting the human element in Scripture can lead to an expectation of a level of expression that is higher than what is customary for a human writer. 8. You might be assuming that if a historical account is incomplete, it must be in error. Sometimes Scripture expresses one thing in different ways, or at least from different viewpoints at different times. A story may be told with more details in one gospel account than it is told in a different gospel. For example, Matthew tended to include more minutiae than Mark, but that doesn't mean one of them got it wrong. 9. You might be expecting New Testament quotations of the Old Testament to be precise. In the ancient world (much like today) it is a perfectly acceptable literary style to give the general idea of a statement without using the exact same words—as long as the meaning is conveyed correctly. Although New Testament writers cite the Old Testament many times without directly quoting it, the New Testament writers never misinterpret or misapply it. 10. You might be assuming that divergent accounts are false ones. Just because two different writers tell the same story with some differing details, doesn't mean their accounts are mutually exclusive. For example, skeptics often note that in the story of Jesus' resurrection, Matthew's account says there was one angel, while John wrote that there were two. Matthew did not say there was only one angel. Contrary to the critics, this is not a contradiction. 11. You might be presuming that the Bible approves of everything it records. This is another hermeneutical no-no. Many books in the Bible are historical in nature and do not make moral commentary on every situation they report on. For example, the Bible records people's lies, David's adultery, and Solomon's polygamy—but it does not condone or promote these actions. The truth of Scripture is found in what the Bible reveals, not in everything it records. It records accurately and truthfully even the bad behavior of human beings. 12. You might be forgetting that the Bible uses nontechnical, everyday language. The Bible was written for the common person of every generation and came long before modern discoveries of science. This does not make the Bible "unscientific," but simply "prescientific." When Joshua records the "sun standing still" in Joshua 10:12, it's no more "unscientific" than speaking of the sun "rising" in Joshua 1:16. For a modern example, turn on your local weather channel, and you will hear your meteorologist referring to the daily "sunrise" and "sunset." 13. You might be presuming that round numbers are inaccurate. Like most ordinary speech, the Bible uses round numbers. For example, it explains the diameter as being about one-third of the circumference of something. According to modern standards, it may be imprecise to speak of 3.14159265 . . . as the number three, but it is not incorrect for an ancient, nontechnological people. 14. You might be forgetting that the Bible uses literary devices. As we noted earlier, God used human agents to write the Bible, and each book has a unique genre and cultural context. Human language includes many literary devices such as poetry, parable, allegory, metaphor, hyperbole, satire, and figures of speech—and naturally, these will all be found in the Bible as well. 15. You might not be taking into account that only the original writings (not the copies) are without error. There are close to 6,000 copies of the New Testament in Greek, and about 19,000 copies in other languages. Among these copies there are variations such as spelling differences, word order changes, and grammar discrepancies. The vast majority of these variations don't change the meaning of the text at all, and there is not one that affects any cardinal Christian doctrine. I have written about this here and here. 16. You might be confusing general statements with universal ones. Some statements in the Bible are more like general principles than actual promises of God. For example, the book of Proverbs is often misunderstood to make universal statements, with no exceptions. However, proverbial sayings, by nature, simply offer guidance and general wisdom—much like the modern saying, "An apple a day keeps the doctor away." No one expects that eating an apple a day will literally keep you from ever having to see a doctor! 17. You may not realize that later revelation supersedes earlier revelation. There is a principle utilized in Scripture called "progressive revelation." It basically means that God didn't reveal everything at once, and had different commands for different people at different times in His overall plan of redemption. Skeptics often confuse a change of revelation with a mistake. For example, a parent may tell a young child to never touch a stove. When the child is older, the parent may allow the child to use the stove after proper instruction and training. This is not a contradiction, but rather, a progressive revelation. If we think we have found a mistake in the Bible, it might be wise to consider that it may not be that we know too much about the Bible, but too little. As St. Augustine rightly noted:

In other words, if I think there is a contradiction in the Bible, it is I who have made the mistake.... not the Bible.

*Augustine, Reply to Faustus the Manichaeans, Book XI, 5.

4 Comments

Daniel Hawkins

9/12/2017 06:11:18 pm

18. Assuming that the Bible was meant to be free of all errors in the first place.

Reply

Alisa Childers

9/12/2017 06:40:11 pm

Hi Daniel, thanks for your comments. I didn't suggest that we should build our entire faith on the inerrancy of the Bible, nor did I suggest that if the Bible isn't 100% true it's worthless. Honestly, it's difficult to even interact with your comments because there are so many assumptions and straw man arguments. I can't see how the points I've made (which are basically just explaining good hermeneutics) are choking the life out of the text with "ridiculous restrictions."

Reply

Daniel Hawkins

9/12/2017 09:00:54 pm

Fair enough. You indeed did not say that, and I suppose one could see what I am commenting being similar to building a straw-man. I will admit that I am indeed extrapolating from your comments and posts what seems to be a likely framework of belief and hermeneutics that you are operating in based on my studies and interactions with other Christians. This is because I am not only trying to interact with you, but a the community of many different people who have been raised in a fundamental evangelical culture that are reading your posts. Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed